‘What’s up with the monkey balls?’ The story of Pittsburgh’s weirdest tree

It’s a tale of woolly mammoth poop, agricultural innovation, and evolutionary anomaly.

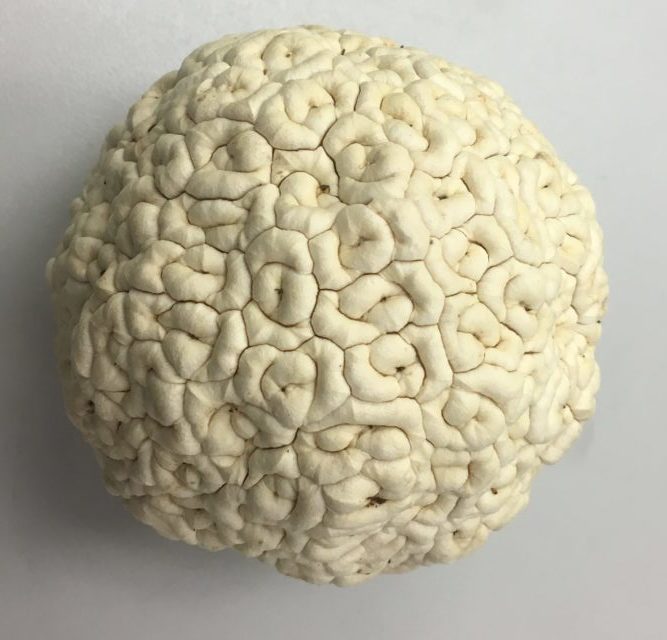

Photo Credit: Joe Stavish, Tree Pittsburgh

Shh … nobody tell the monkey ball trees.

Their dense, sticky fruit used to feed woolly mammoths 10,000-some years ago. The giant creatures are gone now, of course, but the trees don’t know that — and who among us would want to break their arboreal hearts?

So the trees continue each fall to drop their rubbery, green, brain-shaped fruits, assuming woolly mammoths or giant ground sloths will devour and digest them, spreading their seeds across the land and helping the trees expand their timber empire, according to Joe Stavish, community education coordinator at Tree Pittsburgh.

Growing up in Canonsburg, Cindy Toth remembers that “as children, we played with monkey balls and threw them in the woods. My dad put them in the basement and said they kept bugs away.”

Thinking back on the “unusual” trees inspired her to turn to The Incline and asked:

What’s up with the monkey balls?

“That sounds like a “Seinfeld” bit: ‘What’s the deal with monkey balls,’” Stavish said.

In the life of a tree, 10,000 years isn’t very long, and evolutionarily, the trees haven’t figured out yet that the fruits they spent months growing now plunge the ground to be smashed by cars, thrown by kids, tucked into basements for spider control, used as Halloween decorations, or simply left to rot.

What’s in a name?

The tree is officially named the maclura pomifera, and also goes by osage orange (that’s oh-sage, not aw-sage), hedge apple, horse apple, bow wood, yellow wood, or monkey brain tree. But many of its nicknames are confusing, because it’s not an orange or an apple tree, Stavish said.

“It’s a tree that has many common names,” Stavish said. “I don’t think anybody knows why the monkey ball name came about.”

Maybe the name is some reference to monkey genitalia, he said, which are sometimes colorful, but the hypothesis can’t be proven. So the name “monkey ball” isn’t the scientific name, but it’s a Pittsburgh phrase, so in this article, we’re going to continue to refer to it as any yinzer would.

From dinner to bows to fence posts

The fruits — the monkey balls, if you will — weigh 1 to 5 pounds and are generally about the size of a baseball but sometimes can be as big as a football. “Only female trees produce monkey balls, a collection of flowers known as a “multiple fruit,” explained Bonnie Isaac, collection manager of botany at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

“The green fruits are basically a ball of latex, and they’re not edible to humans,” Stavish said, adding that “if you ever cut one open when they’re fresh, they’re white sticky glue. There’s no other trees that produce a fruit like that.”

When they fall to the ground around early October, they now decompose and turn to mush.

But the trees date back nearly 13,000 years, even before the Ice Age, and at that point, its fruit served as breakfast, lunch, and dinner for woolly mammoths in the central United States.

Mammoths, apparently, didn’t seem to have discerning palates. The gigantic mammals swallowed the fruit whole, rather than chewing up the seeds, meaning their waste perfectly preserved the seeds, allowing the trees to sprout in new places.

The trees, it seems, never learned that their metaphorical dining room was empty.

“It’s a tree that doesn’t really know that the mammoths have gone extinct,” Stavish said.

After mammoths, humans found new uses for the trees. The Osage Nation, a Native American tribe, used the trees’ orange-colored, rot-resistant wood to make bows.

“It was a very strong wood, and it was very flexible, which you need for a bow,” Stavish explained.

Eventually, Lewis and Clark found out about the trees when they traveled into St. Louis and sent some specimens to Thomas Jefferson, Isaac said.

“As agricultural development began in the 1800s, farmers coveted the trees’ thorny exteriors for fence posts and planted the trees in a line to create a natural fence keeping animals in their fields and other animals out,” Stavish said. Farmers planted millions, spreading the tree from its native land of Texas, Arkansas, and Oklahoma across the country to places like Pennsylvania.

“On the plains, the trees also provided a shield to protect crops from strong winds,” added Brian Wolyniak, extension educator of urban and community forestry for the Allegheny County Penn State Extension.

Once barbed wire was invented, tree-lined fences fell out of popularity, though you can still find some around the Pittsburgh area that clearly once lined the perimeter of a property.

“Now, the trees, which range from shrub size to 40-feet tall, are seen as a messy tree since they don’t grow into a nice shape,” Stavish said.

But despite its ugly duckling exterior, he said, “It’s a wonderful tree and it has a unique history. … It’s a great tree that we should still have in our urban forest.”

How are the trees used today?

Today’s wildlife don’t eat monkey balls.

“Deer, elk, and moose don’t like the taste of the latex,” Stavish said.

“Plus, the fruit can be a choking hazard for cows,” Wolyniak said.

“At the end of the winter, though, animals sometimes get desperate for food. In those bleak months when everything else is gone, local critters, such as squirrels, will pick the seeds out of the mush,” Stavish said. “The tree was really evolved for those extinct animals.”

“I have a row of them in my front yard, and spiders will build their webs right over them, but there’s still people who will swear by it,” Isaac said. As for humans, they collect the fruits and put them in their basements to deter spiders and insects.

“It’s not scientifically proven, but the oils in the fruit may act as a natural insect repellant — that is, until the fruit rots and attracts fruit flies,” Stavish said, adding, “The fruits also make excellent Halloween decorations, given their creepy look.”

But not to rain — er rot — on your parade, Isaac cautions: “They’ll rot just like everything else eventually.”

Before they start decomposing, kids enjoy rolling them down hills — or throwing them, as our question-asker remembers.

“They’re definitely a weapon of war for the neighborhood children,” Stavish said.

The orangish wood, which Isaac describes as “absolutely gorgeous,” still makes excellent bows, tool handles, and even furniture.

Homewood-based Urban Tree LLC rescues trees that are being cut down and turns them into furniture — that includes monkey ball trees.

The hard but flexible wood makes a strong exterior-grade material for things like outdoor playgrounds, benches, or chairs, which the company has built at local schools and Phipps Conservatory, Urban Tree partner Jason Boone said.

“It’s not a very common find for material. … It doesn’t typically get very big and it doesn’t grow very straight to make lumber out of it,” Boone said. “It is pretty nice when you can finish it out.”

Find a monkey ball tree near you

Want to see one in real life?

Hunt for them atop Mt. Washington, near Construction Junction in Point Breeze North, or by the Blue Slide Park playground in Squirrel Hill.

“They’re definitely not a common tree,” Stavish said. “Some of them are definitely survivors of the old fences.”

Photo credit: Bonnie Isaac, Carnegie Museum of Natural History

Though the plants quickly take root, few people plant them these days.

“It’s kind of an old-fashioned kind of thing,” Isaac said. “I’ve not seen a lot of recent plantings. The really old farms — that’s where you see them.”

People do ask about them, though, so Isaac keeps some “spectacular” freeze-dried monkey balls in the museum’s collection, though they’re not currently on public view.

“I have a few people always asking if they can see the freeze-dried monkey balls,” she said.

Though the trees didn’t originate here, they’ve certainly become a part of the common lexicon and natural landscape.

“While it’s not necessarily native, it’s kind of taken hold,” Wolyniak said. “It’s not something we eat. It’s not something animals eat. It’s an interesting anomaly in a sense that they’re still around.”

Written by Rossilynne Culgan

Ask us your questions about Pittsburgh and our region – hello@theincline.com