Pittsburgh has a bridge and a trail with her name, but what do we actually know about Rachel Carson and her time in the city we call home?

For those unfamiliar, Rachel Louise Carson was a native Pittsburgher, marine biologist, author, and conservationist. She’s best known for writing “Silent Spring,” a book detailing the dangers of pesticides. The text went on to provoke the passage of the Clean Air Act, the Wilderness Act, and Endangered Species Act, as well as the development of the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970.

Carson was a pioneer of the environmental movement and led a paradigm shift where Americans started looking at themselves as being a part of nature rather than outside of it. In other words, she helped advance the idea that humans may not be able to exert full control over nature, and may in fact actually be at its whim.

“She translated science into not just everyday language, but beautiful poetry,” Mt. Washington native Patricia DeMarco said. DeMarco is a Rachel Carson scholar and the author of the book “Pathways to Our Sustainable Future – A Global Perspective from Pittsburgh.”

“She is my hero. She was amazing as a teacher, and the lasting nature of her words is so relevant to what’s going on today,” DeMarco said.

📸: Rachel Carson’s year book photo, 1929. Photo courtesy of Chatham Archives.

The Incline decided to observe Earth Day by honoring Carson and her connection to Pittsburgh. We took a deep dive into the archives at Chatham University, formerly Pennsylvania College for Women, where she graduated magna cum laude in 1929. Thanks to Chatham archivist Molly Tighe for letting us dig through her files. Here’s what we found:

Her love of the natural world started along the Allegheny River.

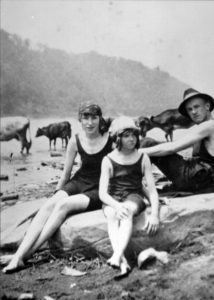

📸: Carson with older siblings Marian and Robert along the beach of the Allegheny River with cows in the background. Photo courtesy of Chatham Archives, public domain.

The same river where her namesake bridge now hovers is also where she first dipped her toes into exploring nature. Rachel was born in 1907 and raised on a small farm in Springdale, Pa., where she grew up alongside two siblings and lots of animals.

“She didn’t grow up in a happy time,” DeMarco said. “Her family was poor, and she had a close connection to the outside world because people were overbearing in her family.”

As a child, Carson would take her dog for walks into the nearby woods and find nesting birds. She began writing stories about these adventures at eight and had her first story, “My Favorite Recreation,” published in St. Nicholas Magazine at age 14.

“She got paid $10,” Patricia said. “That was the start of her dreaming of becoming a writer.”

She first attended Pennsylvania College for Women as an English major

📸: Rachel Carson’s poems “Triolet” and “March” published in The Arrow in 1928. Photo courtesy of Chatham Archives.

Carson had a knack for writing from a young age, which is why she began her education as an English major. She was really successful at it, too; The Chatham archives hold a variety of poems and articles of hers published in the school newspaper, The Arrow.

But when Carson became interested in science, thanks to her professor Mary Scott Skinker, she switched majors and had to double up during her junior year to meet graduation requirements, Chatham archivist Molly Tighe said.

“Her biology teacher was the coolest, most elegant person on campus,” DeMarco said. “She always wanted to write, but now she knew what she wanted to write about.”

Carson’s connection and deep love for nature was clear even from her earliest writings — even while working toward another occupation, her true calling was audibly beckoning.

In an essay titled “Who I am and why I came to PCW.,” she wrote:

“I am seldom happier than when I am before a glowing campfire, with the open sky above my head. I love all of the beautiful things of nature, and the wild creatures are my friends. What could be more wonderful than the thrill of having some little furry animal creep closer and closer to you, with wondering, but unafraid eyes?”’

However, Carson’s family didn’t share her enthusiasm and were disappointed when she changed majors.

“She had prospects of becoming an English teacher, but in biology, there were pretty much zero opportunities for women at the time,” DeMarco said. “She had to create her own space and make her way in a man’s world, and she did so brilliantly.”

Carson went on to earn a summer scholarship to the Woods Hole Marine Biological Laboratory in Massachusetts and got a scholarship from Johns Hopkins University for a M.A. in Zoology.

She loved sports, just like Pittsburgh does.

📸: Rachel Carson standing in the back row, second from the right, with the Honorary Field Hockey Team for Pennsylvania College for Women. Photo courtesy of Chatham Archives.

In the same essay where she professed her love of nature, Carson also touched on her appreciation of athletics. She wrote, “I am intensely fond of anything pertaining to outdoors and athletics…Although I do not excel in sports, I enjoy swimming, tennis, hiking, riding, and basketball. I am an enthusiastic spectator at football and other games.”

She was on the honorary field hockey team at PCW, as the school didn’t offer intercollegiate sports at the time — only intramural. Whether or not she excelled at sports is up for debate; Carson was the goalkeeper for the “Navy” team (the junior class) in its final match and helped to defeat the “Army” team in 1928.

“I think this is just another example of her notable perseverance,” Chatham archivist Molly Tighe described Carson as someone who put herself out there for the sake of fun and love of the game.

Carson had a special spot outside the city where she liked to study nature.

📸: Crouse Run Nature Reserve, photo courtesy of Molly Tighe.

Carson could often be found studying wildlife in a 22-acre valley in Hampton Township about 30 minutes outside of the city. Today, the spot is known as the Crouse Run Nature Reserve.

During her college days, she took the Butler Electric RR from Pittsburgh to examine the biological diversity of the valley’s flora and fauna.

At the time, the location wasn’t as esteemed as it is today. Now it’s one of the few spots listed as an “exceptional” level in the Allegheny County Natural Heritage Inventory.

The reserve’s website shares a revealing 1969 quote from Roger Latham, an outdoor writer for the Pittsburgh Press.

“In the valley bottom spring wildflowers reach their peak abundance and fullest variety. Trillium grow in such profusion as to form carpets of flowers in some places. Mixed with these in early spring are dog-toothed violets, hepaticas, spring beauties, dutchmen’s breeches and others.”… “This unique and valuable acreage in Allegheny County, where the advances of civilization have all but eliminated natural areas, is well worth preserving for future generations.”

A 33-mile trail passing through the valley was renamed in Carson’s honor in 1975. While this information wasn’t available in the archives, Chatham archivist Molly Tighe shared her knowledge and even a photo from a visit she made there — that’s it right above!

Her achievements were celebrated by Chatham, but less so by the steel industry city.

📸: A letter of congratulations to Carson from Chatham’s president, Edward D. Eddy Jr. Photo courtesy of Chatham archives.

Carson’s letter correspondence with Chatham’s president shows that the school took pride in its alumna’s accomplishments, like when she won the Audubon Medal or was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1952. (And as anyone who studies or teaches at Chatham will tell you, that pride is still present at the college today.)

See the note above where Edward D. Eddy Jr. said: “If you keep winning these honors, I’ll be spending all of my days in writing notes of congratulation.”

Although it was where Carson called home, Pittsburgh was still a steel industry town and had a much chillier reception to her work. For that matter, many in the United States took issue with her writing: At the height of the Cold War in 1961, opponents of “Silent Spring” attacked Carson personally and accused her of being radical, unscientific, or hysterical.

Controversy over Carson’s work pervades in Pittsburgh even today. DeMarco recently served as the director of the Rachel Carson Homestead in Springdale; she said that people were still telling her that her organization’s namesake was responsible for the crash of the steel industry.

“They looked at preserving the environment as the enemy of jobs,” DeMarco said. “The only way we are going to have a future is if we make decisions that support our life support systems first. The key thing that Rachel Carson gave us is our sense of obligation to the next generation; thinking in terms of the laws of nature, which are not negotiable, and living with them instead of having control over them.”

In her last days, she kept her illness hidden, but it was hidden from her too.

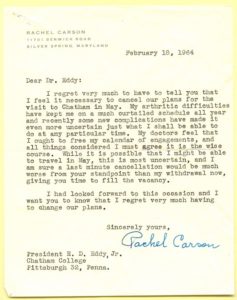

📸: A visit cancelation letter from Carson to Chatham’s president in 1964. Photo courtesy of Chatham archives.

Carson cited “arthritic difficulties” in a letter she sent to Eddy canceling a planned 1964 visit to Chatham. Sadly, her true ailment was much more serious.

Eddy wrote back, “There will be another day and another year when you can come to Chatham.”

But there wouldn’t be.

A year earlier in June 1963, Carson delivered a statement before Congress raising awareness of the environmental hazards of pesticides as well as their link to diseases like cancer. Below is an excerpt from her speech:

“The contamination of the environment with harmful substances is one of the major problems of modern life. The world of air and water and soil supports not only the hundreds of thousands of species of animals and plants, it supports man himself. In the past we have often chosen to ignore this fact. Now we are receiving sharp reminders that our heedless and destructive acts enter into the vast cycles of the earth and in time return to bring hazard to ourselves.”

Photographs taken during her speech show that Carson was wearing a wig to conceal her ill health. She had breast cancer, and was dying of the very disease she was fighting to prove could be traced back to these harmful chemicals.

But even she wasn’t aware how dire her diagnosis was. She’d previously had a breast tumor removed in 1950, and there was no further treatment suggested at the time.

“Because she was a woman and wasn’t married, her doctors wouldn’t talk to her about it,” DeMarco said. “She learned too late. She already had stage 4 metastatic cancer.”

Not only did Carson square off against the industrial economic powers of the time, but she had to fight medical professionals simply to learn the truth about her illness. But it’s not a mystery why she kept this information secret from the public — if the chemical industry found out, they would use her illness to question her scientific objectivity. In the hopes of manifesting a better tomorrow for others, she kept her own battles at bay.

And a better tomorrow did come: Because of Carson, generations of scientists, environmentalists, and writers were inspired to advocate for Mother Earth — much like Patricia DeMarco.

“I would like to see Pittsburgh recognize her ethic of care for the next generation. She was so inclusive in her love and understanding that we are all connected and our livelihood depends on the living Earth,” DeMarco said. “We have so much to learn from her.”